Arindrajit Basu, Fellow, Datasphere Initiative

Introduction

Negotiating and balancing legitimate competing and often complex interests advanced by multiple stakeholders is inherent to the concept of the datasphere – the complex system encompassing all types of data and their dynamic interactions with human groups and norms.

Trade agreements have often been used by powerful states and their private sector actors too, at times, steamroll obligations onto other states and their citizens and organizations (Chimni, 2006). This top-down approach – where countries create new norms based on what is decided in bilateral or multilateral trade agreements – often occludes much-needed conversations and potential frameworks developed domestically from the ground up.

This has been true for technology and internet regulation, and can now also be said to be true for data governance. Provisions in bilateral and multilateral trade agreements have impacted data governance through multiple normative frameworks: on e-commerce, flow of information, privacy, telecommunications, and technology more generally. One example of these provisions that have been strongly pushed by global north countries relates to the disclosure of software source code as a condition for market access. The debate on source code is only one example of how infrastructure, international institutions, and various stakeholders compete and co-operate to assert their interests in and responsibly unlock the value of data.

In this blog post as part of my Datasphere Initiative Fellowship, I unpack the competing developmental, regulatory, and business interests surrounding this issue and how it can be related to the concept of the datasphere. I argue that trade agreements that arbitrarily restrict domestic policy deliberations may harm the much-needed dynamic multi-stakeholder approach to responsibly unlock the value of data for all by imposing top-down normative codification.

What is source code? What legal protection does it receive?

Source code refers to the human-readable instructions written by programmers to instruct a machine to perform a certain task (Irion, 2022). Some of these tasks include the algorithmic processing of large amounts of both personal and non-personal data to produce outcomes that have immediate consequences on the lives of individuals and communities. Simply put, in the context of the datasphere, source code is an essential infrastructure that is used by businesses to collect, use, process data, and unlock value. Traditional understandings of source code are very broad and include Application Programming Interfaces (APIs.) (Slok-Wodkowska, Mazur, 2022). APIs are gateways through which the algorithm receives its input data and queries and produces output that is also included within source code.

Source code is not entirely protected by intellectual property codified through the World Trade Organization (WTO) Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement (Slok-Wodkowska, Mazur, 2022). While TRIPS interpreters point to copyright as the appropriate means of protecting source code, there is still much debate on the extent to which IP actually protects source code. (Slok-Wodkowsa, Mazur, 2022). Further, copyright does not protect the idea behind the source code, only unauthorised usage or copying. The idea may be protected by patent under Article 27 of TRIPS but the inventive character required for patentability may be questioned, leaving some freedom for WTO members to refrain from unconditionally granting patents to source code. Protection through trade secrets (Article 39 of TRIPS) offers the strongest protection to source code but does not offer protection against discovery by fair and honest means such as independent innovation or reverse engineering.

Source code in trade agreements

Given the uncertain protection under intellectual property laws, some countries have sought to codify protection for source code through trade agreements to protect the interests of their private sector operating in different markets. Examples of Bilateral trade agreements with such measures include the Japan-Mongolia Economic Partnership, EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement, Peru Australia Free Trade Agreement, and larger plurilateral agreements include the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTTP) and the United States-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement. Further, the Joint Statement Initiative attempting to push through a WTO agreement on Electronic Commerce also mooted provisions on source code disclosure modelled along the lines of the provision in the CPTPP (Basu, 2021).

On the basis of the provisions in these trade agreements, a party – a state – cannot require access to the source code as a condition of import, distribution, sale, or use of that software or of products containing that software on its territory.

However, all these agreements do bring exceptions to this non-disclosure rule. For instance, a party to that trade agreement can mandate disclosure for ‘public interest’ and security reasons, such as when a source code is a crucial element of that state’s critical infrastructure.

However, even these exceptions have limitations to them. General exceptions drawn from the umbrella WTO agreements or those exceptions present in the multilateral trade agreements, also generally do not favour the party invoking the exception (that is the government mandating access to source code) as the burden of proof falls on that party. In fact, thirty-eight out of the forty cases where the general exception has been considered by WTO dispute settlement authorities failed (Rangel, 2022). Finally, while access by a tribunal or regulatory body may be permitted under an exception when there is a court case filed against the private sector actor designing and deploying algorithms, this approach prevents general conformity assessments and audits that the government may mandate through legislation and policy.

On the other side of the spectrum, the China-driven Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership notably does not include a similar provision on non-disclosure of source code. Thus, when a state comes to join the RCEP, China – or any other party to the RCEP – can indeed mandate the disclosure of source code.

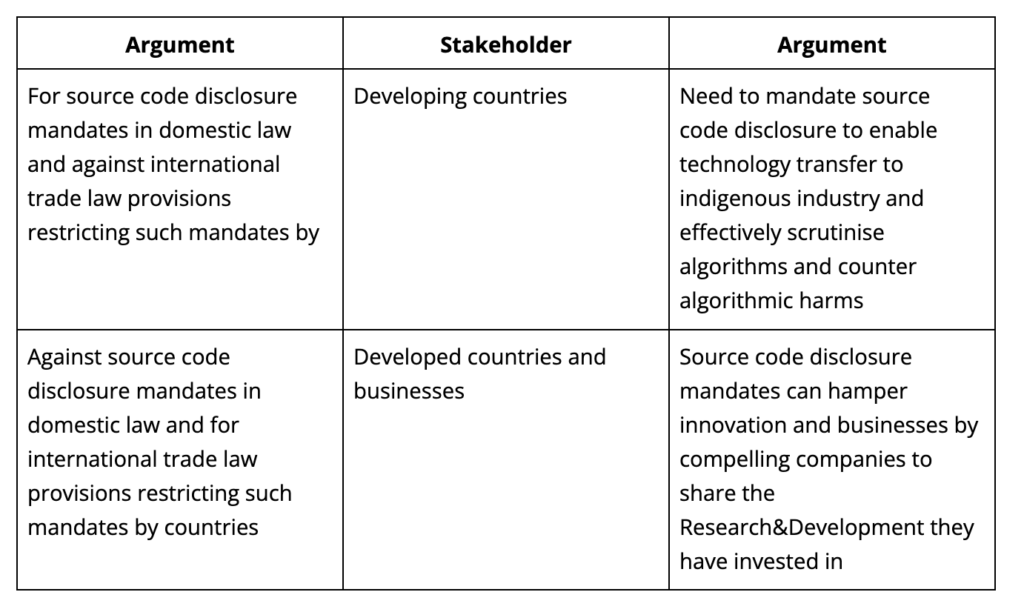

Competing interests around source code disclosure

The most poignant reason for the non-sharing of source code provisions in trade agreements is the ambition of governments – supported by domestic private interests – to prevent forced technology transfers (Irion, 2022). Forced technology transfers refer to practices where a country conditions market access and investment by another country and its private players disclosing trade secrets or other commercially valuable information, such as source code. The forced divulsion of proprietary source code is argued to be extortionate by businesses. The argument here is that forced technology transfers through weak bureaucratic justifications can impede investment and innovation.

This practice has come into the limelight as one of the issues among ongoing US-China tensions (Qin, 2019). China has been accused by the US of using administrative measures – allowed in the Chinese trade agreements – to coerce US firms to transfer technology to China-based firms.

The immediate response and competing interest here is rooted in geopolitical and developmental aspirations. Technology transfers can support development and enable countries to potentially leapfrog (Yayboke, Crumpler, and Carter, 2020) by augmenting the capacity and know-how of local companies, thus supporting bridging the digital developmental gap and fostering more competitive markets worldwide. Further trade provisions firming up source code protection are fundamentally incompatible with the proliferation of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), which is necessary for furthering digital access, openness, and innovation in the developing world. Countries such as South Africa and India have FOSS policy requirements which essentially imply that proprietary software can only be used once source code is disclosed (Irfan, 2019).

Second, many argue that access to source code is often an integral aspect of algorithmic audits and forms a part of conformity assessments (Irion, 2022). Provisions restricting mandatory source code disclosure restrict the rights of governments to foster transparency in and regulate algorithmic decision-making to safeguard the rights of its citizens.

Source Code, Algorithms, and Data Derived Harms

Going forward, I suggest two separate takeaways. First, trade agreements must not scuttle various algorithmic transparency efforts around the world. There are several global and domestic efforts underway to evaluate algorithms so that they do not use personal or non-personal data to cause citizen harm. One of these methods is by accessing and evaluating the source code underpinning an algorithm. Algorithmic transparency efforts are dynamic and complex with technical, ethical, and legal experts attempting to work through frameworks that balance innovation, efficiency, and rights at the domestic level (Larrson and Heintz, 2020).

Second, prematurely scuttling domestic and transnational policy debates on critical questions related to the future of the datasphere, such as algorithmic transparency, through trade agreements does not protect innovation or further global cooperation. It also alienates countries from the developing world such as India and South Africa from engaging with and ultimately signing trade agreements for fear of ceding control of their domestic-policy making space for plurilateral trade agreements (Basu 2021).

Restricting domestic source code disclosure provisions artificially attempts to solve a complex problem without addressing its root causes or considering more tailored situations. For instance, a more concretely designed enforcement framework could target illegitimate forced technology transfers of source code that do not aid development in any way.

Conclusion: How this relates to the datasphere and recommendations for moving forward

Trade agreements are part of the norms that compose the datasphere. The actions of actors pushing for certain positions via trade agreements impact the chain of value creation and how that value is distributed.

Source code is an essential component of the data layer that makes up the essential digital infrastructure of states and their citizens. Source code is essential to the way data is processed and value is created. Source code is also at the center of various harms that – in many cases – can be noticed only after the fact (e.g. bias in the results of algorithms). In this post, I have discussed some of the legitimate interests and arguments at play in this specific battle for access, all of which could be used to unlock or undermine the value of data for different stakeholders, depending on the context. A summary is shown in Table 1.

Norms must endeavour to balance competing interests articulated by the wide range of stakeholders making up the datasphere, both public and private. Simply put, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ assessment or opinion that can govern the datasphere and any responsible policy assessment must engage with the range of competing interests and stakeholders.

In the context of the datasphere, trade agreements are institutionalised norm-creation processes that could solidify mechanisms for global governance. However, in order to responsibly unlock the value of data, broader and continuous assessment, and multistakeholder oversight could play a positive role in understanding the impact of such trade agreement provisions and how they relate to unlocking the value of data for all, and not only to companies and countries in the global north.

Over the course of my fellowship, I will focus on cross-border data flows and their related restrictions – another issue that has been a critical issue in global trade debates. Like the debate on source code, there are different competing interests and arguments advanced by stakeholders. By empirically evaluating these arguments and interests, I will contribute to the question of how trade agreements can responsibly foster norms so that states can frame appropriate policies and individuals, communities, and businesses can assert their rights and responsibly unlock the value of data for all.

References

Basu, A (2021), ” Can the WTO build consensus on digital trade?” Hinrich Foundation, Available at:https://www.hinrichfoundation.com/research/article/wto/can-the-wto-build-consensus-on-digital-trade (Accessed January 2, 2023)

Irfan, M (2019), “Data Flows, Data Localisation, Source Code: Issues, Regulations and Trade” (CUTS International Geneva)/https://www.cuts-geneva.org/pdf/WTOSSEA2018-Study-Data_Flows_Localisation_Source_Code.pdf (Accessed January 2, 2023)

Chimni, B.S.,” Third world approaches to international law: A manifesto,” International Community Review 8:3 /https://www.jnu.ac.in/sites/default/files/Third%20World%20Manifesto%20BSChimni.pdf (Accessed February 22nd, 2023)

Irion, K, (2022)Algorithm off-limits, FaccT’22 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability and Transparency, Seoul, Republic of Korea, June 2022.https://dl.acm.org/doi/fullHtml/10.1145/3531146.3533212 (Accessed January 2, 2023)

Larsson S and Heintz F, ” Transparency in Artificial Intelligence,” Internet Policy Review 9(2),https://policyreview.info/concepts/transparency-artificial-intelligence (Accessed January 2, 2023)

Rangel D, “WTO General Exceptions: Trade law’s faulty ivory tower,” Public Citizen, Available at:https://www.citizen.org/article/wto-general-exceptions-trade-laws-faulty-ivory-tower (Accessed January 2, 2023)

Slok-Wodkowska M and Mazur J (2022) ” Secrecy by default: How Regional Trade Agreements Reshape Protection of Source Code,” Journal of International Economic Law 25 (1) https://academic.oup.com/jiel/article/25/1/91/6534278\ (Accessed January 2, 2020)